A NOTE TO THE READER

The poems collected in this book are by a woman who more than anything loved language. My mother, Maeve Butler Beck, loved the sounds of words in all their permutations—their eccentric origins, possibilities, and reverberations. She sensed the world around her in musical language: The song of the thrush, the dip, dip of a paddle in water, and soughing of wind in balsam branches were a sacred language she understood in a visceral way.

Maeve was somewhat shy, more at ease playing word games, singing, or quoting a line of poetry than engaging in small talk. She liked people who made her think and laugh, and would hone in on someone who was sad or bereft to share her laughter with them. She was ill-at-ease at gatherings of high society and loathed having to shop for clothes, but she loved playing practical jokes, traveling, carrying out seasonal rituals, and inspiring young people to learn about the wonders of the world around them.

As a young woman Maeve envisioned a career as a published writer and a teacher of literature. But like her friends she got married two years after college, shortly before her husband went off to war. Seven years later she had three children and was “immersed,” she wrote in a letter, in the “turmoil of the mop and the broom.”

Her greatest source of anxiety after I, her second child, was born was whether she could be a good mother and also stay true to herself as a writer. That anxiety never went away but she came up with strategies to deal with it, one of which was to write the poems in this collection.

In her first decade of motherhood Maeve devised ways of weaving her writing into the silent spaces when my father was at work and my brother and I were either taking naps or in nursery school. As we got older those spaces shrank. By the time I was a teenager she had little privacy or time for herself.

The crossroads in our lives was the winter I turned fifteen and got my driver’s license. I was fledging, either gone from the house or shut in my room, not interested in sharing my life with anyone but my friends. My mother’s strategy for worrying about me and dealingwith my rebellions was to confront them in her own vernacular: When I went out in the evening she did not lecture me before I left or or sit up waiting for my return. Instead, when I came home I found a poem on the back of a chair, on the stairs, on the edge of the sink in our bathroom, or slipped under my bedroom door. If the poem was gone the next morning Mom knew I was home safely.

I call these creations of Maeve’s “Home” poems, since no matter how far afield the subject of the poem might stray it was ultimately about my leaving and returning home. She did not, for the most part, make drafts or copies of these poems, and with only a couple of exceptions she did not date them or give them titles.

Home poems were written in motley forms of poetry that combined absurdity, beauty, news, and whimsy. In the midst of their lyricism they might also make reference to places, people, homework, chores to do, current events, and when the car would or would not be available. Home poems were often funny, designed to catch my attention or bring up important topics in a roundabout way. They were also a vehicle by which my mother demonstrated the nuances of language, rhythm, and line in formal metric poetry. If I was unaware of her subtle teaching she did not let that stop her, since the poems were as much for her survival as my enjoyment and edification.

Writing Home poems was an oasis in my mother’s day—a savored moment in the evening when she could sit down and compose an ephemeral but fully-realized poem, turning the mundane into the sublime if only for a moment. She was in her element writing Home poems—spontaneous, funny, inventive, and contemplative. And since the natural world was Maeve’s touchstone, the changing seasons were always present in the poems: Flowering spring, a summer cricket’s chirps, the changing colors and stark branches of fall, and winter’s deepening snows.

My mother subsequently wrote Home poems for my brothers when they were in high school or lived at home, but she continued writing Home poems to me because I was the only one of her children who in her lifetime left Minnesota and only came back to visit; and I was her only daughter. She wrote me 150 Home poems over the course of eighteen years, beginning in the winter of 1962 and ending just before her death in September, 1979.

POEMS IN THE BOOK

1961-1962 HIGH SCHOOL: FRESHMAN YEAR AND SUMMER

I should think that, 57

Methinks that now the little miss, 60

My children, a slight kiss is welcome, 61

Oh, Peggy, now as you return, 62

When you come back we all will be, 63

This is a letter for my daughter, 64

Our little girl is not home, 65

Our little girl that from the dark, 66

It will be late when you come home, 67

Dearest Peggy as you enter, 68

For Margaret—in the reach of summer, 69

1962-1963 HIGH SCHOOL: SOPHOMORE YEAR AND SUMMER

Dearest Peggy welcome home, 72

For the certain type who entering late, 74

Peggy, welcome to this house, 75

Dearest Peggy: late + soon, 76

Dearest Peggy from this hour, 77

My daughter that the dark has claimed, 78

My child please come inside the door, 79

Now when you come home you will, 80

How sad it was to crunch, 81

What if the daughter coming home, 82

So the girl comes home at last, 83

Margaret wondering hopefully, 85

Childhood times lie now long, 86

Darkness, Lightness, fearless, 87

Iambic Dimeter, 88

Tonight we go back to the trite, 89

To Margaret on Her Return From the Basketball Game, 90

Poem for Peggy, 91

Before the phone destroys, 92

1963-1964 HIGH SCHOOL: JUNIOR YEAR AND SUMMER

The night + Monday morning loom, 95

Dearest Peggy, while you’re gone, 96

Dear Peggy welcome to your bed, 98

Dear Peggy Thank you for your sanity, 99

Dearest Peggy, did the map, 100

Dearest Peggy now to know, 101

Dearest Peggy late + soon, 103

Advance upon this vestibule , 104

Dearest children of our hearts, 105

I wonder if the people know, 106

Dear Peggy + Carl, 107

Sweet Peggy, now the night is dark, 108

Dear Peg, I see the lighted house, 110

Peggy must feel that her hour, 111

Dearest Peg your parents are, 113

That from the theatre she comes in, 114

Dear Peggy when you come , 115

Before I eat my egg + soup, 116

Dearest Peggy Step inside, 117

Dearest Peggy in your roses , 118

Dearest Peggy, welcome home, 119

Of course when one must live, 120

How sad I am you did not sail, 122

When Peg comes back into this room, 123

1964-1965 HIGH SCHOOL: SENIOR YEAR AND SUMMER

Dear Peggy, Here upon this floor, 127

Father and daughter have returned from their duty, 129

After tonight I cannot say, 131

Dearest Peggy, From my couch, 133

We watched the Beanfeed on the screen, 135

Some people call her Marguerite, 136

All right, my daughter, 137

O how the theatre rankles, 138

A daughter should never , 139

Dearest Peggy late or soon, 140

Cavort, collapse or what you will, 141

Dearest Peggy, dear wild child, 142

My daughter in the depth of night, 143

Dearest Peggy yet so near, 144

Enough is said. When darkness falls, 145

I often cried, 146

Dearest Peggy. Please don’t look, 147

The night of trying wet + snows, 148

Perhaps you had to face the diaper, 149

Dearest Peggy, will the days, 150

The booster for the battery is tied, 151

Dearest Peggy from the snow, 153

Dearest Peg with delight, 154

No mail came today. No bad, 155

Dearest Peggy, as I wait + wonder hard, 157

Best enter tranquil as you are within, 158

Dearest Peg Nothing rhymes with half-past-one! 159

Dearest Peg, 160

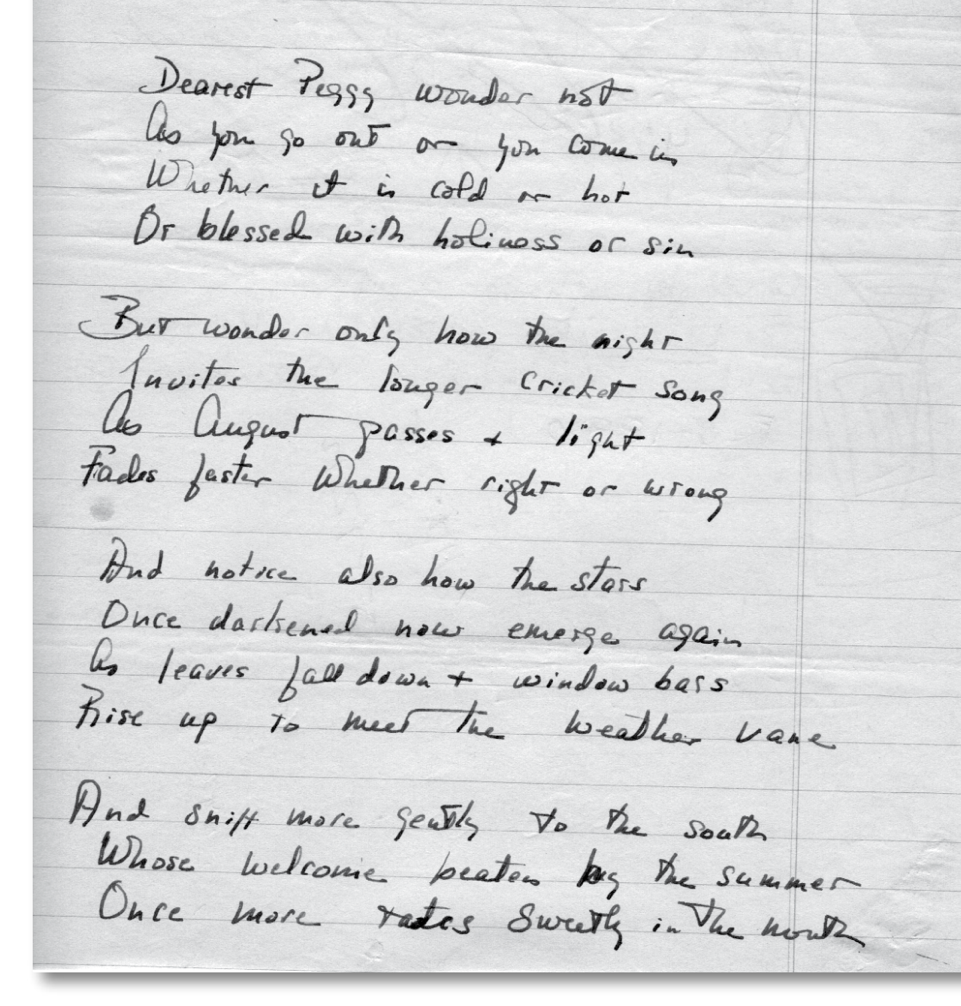

Dearest Peggy wonder not, 161

We say good night to our good child, 162

Who won the game, 163

1965-1969 COLLEGE AND SUMMER/FALL

We wait + hope the night will bring, 167

O my daughter, with what joy, 168

Ici bas, on ne pleure plus, 169

Now, dear Peggy, how I wonder, 170

With limited supplies of ink, 171

The Word, 172

Dearest Peggy, in this room where moonlight often, 175

What a lovely person comes, 177

For the gentleness that comes, 178

Music is not food; it is, 179

When people talk about communication, 180

Perhaps we dedicate this new December, 182

I love each moment of this snow, 183

Tonight you have the snow, 184

1969-1971 JOURNEYS

Bed is a welcoming right now, 187

Instead of wondering about the sea, 188

Dearest children welcome home, 189

Sylvia and Peggy, very dear, 190

Enter with love the end, 192

1972-1974 SANTA CRUZ, CALIFORNIA AND NEW MEXICO

Where the snow night unobserved, 196

Dearest “Pearl” from the bill, 197

Tonight is the first night of fall, 199

The white-throat plies, 201

Dearest Maggie, welcome back, 203

How hard and steep, 205

Whether for left or right, 206

The night comes in the afternoon, 207

Reentering the child’s abode, 209

For Peggy on the 25th of May, 211

Torn by your coming, leaving, 212

Dearest Maggie, 214

Matter. What matter is uncertain, 216

Dearest Peggy, Rhyme, I’ve decided, 217

dearest child, the vex is where, 218

Dearest Mag, you know I am, 220

The moon invisible behind the stars, 222

1975-1979 NAVAJO NATION AND NEW MEXICO

Magwa, 226

Beloved child, 227

However small the room how much we grow, 228

As one hides the pomegranate, 230

If anything can mar, 232

The air is holding, 233

Especially now the, 234

As you depart , 236

Margarita, and Peggy, very dear, 238

Welcome home to this confusion, 240

Interested always in your world, 242

The bird (the White throat returns-, 243

Goodnight sweet child, 244

Afternoon of pleasure, 246

This is a Shakespearean sonnet. Tomorrow there, 247

This here is a Petrarchan sonnet, 248

growing older the first, 249

Tonight no bloom, 250

Augmented Interval, 251

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS, 256

INDEX OF FIRST LINES, 258

Margaret wondering hopefully

Turns out her genius in

Commerce + distantly

Aims for a portrait

Gully + gulch for a sinfully

History belchingly wondering

Where the main currents of

History start, + where the most

Piles of old apple tart

Hidden in cellars +

Bursting with meaningful

Tidings are likely with art,

From the entrance + exit of

Chemically ordered +

Worthy constructed holes most

Likely to fart.

Dactyls are splendidly

Hidden + voluble

Keep them in trust

Find them insoluble

∩__ __ ∩∩__ Ma!

1963. Handwritten. This is the first poem in a five-poem series featuring different meters. The meter in this poem is a dactyl which has one stressed and two unstressed syllables. When scanning a poem Mom used “∩” over an undstressed syllable, and __ over a stressed syllable. Using these symbols I believe the message at the end scans, “I love you very much.”

How sad I am you did not sail

Upon the lake named Bear

but had to sit + chat like quail

on the boatless water stare

Let’s hope that many better days

will bring you weather for the mast

thus erase the vile ways

shove this Sunday to the past.

I like to think that soon a wind

“sits on the shoulder*” of a sail

That you will skip + master mind

through every calm + every gale

I like to think that on a pond

of northern waters, you’ll allow

Your ma to cunningly respond

to tempting waters at the prow

+ hold the tiller some

+grasp the sheet inside her palm

+slip it past a gripping thumb

in answer to the squall or calm.

*Hamlet

1964 Summer. Handwritten. A high school classmate had a place on White Bear Lake near St. Paul where I went to swim and sail a couple of times. However, the “pond of northern waters” refers to Osgood Pond in the Adirondacks. Mom bought a Sailfish boat for the island and hoped I would take her sailing when we went to Camp later that summer.

Dearest Peggy wonder not

As you go out or you come in

Whether it is cold or hot

Or blessed with holiness or sin

But wonder only how the night

Invites the longer cricket song

As August passes + light

Fades faster whether right or wrong

And notice also how the stars

Once darkened now emerge again

As leaves fall down + window bars

Rise up to meet the weather vane

And shift more gently to the south

Whose welcome beaten by the summer

Once more tastes sweetly in the mouth.

Beginning of September, 1965. Handwritten.

Tonight is the first night of fall

the summer’s ending equinox.

The dark and crimson wild whorl

of vines on tree trunks and on rocks

marks unremarked when summer rang

and beetles scurried under bark

and heated torpid creatures sang

their beam of noonday: envy of the lark;

the sultry story and the rains

are over and the fall remains

with enamel in the poplar leaf

and cold nights strengthening belief

in anything until so soon

the empty branches on the sky,

leaves hauled away, the moon

will throw again the tracery—

the mighty branches of the heart

within, the heart without

about the searching end and start

of timelessness, of drought,

dampness and flood, desert, and friend

eternal questions that make whole,

if always asked, that always mend

the hurts and breaches of the soul.

I rode my bike up along the tracks to the railroad trestle before the sun went down. There were some Bad Children up there trying to throw the switch and put things on the tracks as to mess up oncoming trains. When they saw me coming they must have thought I was a plainclothes policelady because they sort of dribbled down the hill. I longed to ask them their techniques and be in on the plot. Since I wasn’t, I removed crap from the tracks and guaranteed survival of the Establishment.

September, 1972. Typed.

Notes on “Augmented Interval”

Fall was in the air when Mom wrote her last Home poem to me. Unlike other Home poems which did not have titles she called this one “Augmented Interval.” Even as a draft I consider it one of her most accomplished poems in any genre. She wrote the poem at Camp in the Adirondacks on the ancient typewriter there and sent it to me from 1610, our home in Minneapolis, after we had left the island where we met for two weeks, me from New Mexico, Mom from Minneapolis, to go our separate ways. In this poem, she uses musical metaphors to describe the end of summer, suggesting that the interval until our next time together would be longer than usual.

Although she inserts typical humorous deflections, the poem has a wistful, misty quality about it, the feeling of what we would call “a Camp day,” when it rains softly all day long, the lake is silent, and “the twisted smoke” drifting from the chimney of the fireplace melds with sharp, piney air:

You are in the turn of weather and tune.

Autumn demands the cello of final wings,

the measured stroke,

the bowing and white dew….(p. 251)

The day she left the island was the last time I saw her.

Augmented Interval

You are in the turn of weather and tune.

Autumn demands the cello of final wings,

the measured stroke,

the bowing and white dew.

Semi quavers fall

that give you back;

lightness, a catching air;

green, blue, and scarlet drifting.

This ivy twisted like the treble clef

climbing the frets and tugs of scabrous bark

is music of the diminished step and singing* lake;

or pluck of pewit in the sand.

This is the return of twisted smoke—

the far song you made. I hear

the creak of buck pods**opening with rain;

musk smell presage of dusk.

Scores of summer settle, scattered

over staves, patterned as the leaves

that quiver

in whole notes and in halves.

- bad word here

- * no such things exist

August, 1979. Typed. An augmented interval is a musical term meaning a major interval where the top note

has been raised by one half-step. A semi-quaver is a sixteenth note